In the early 1980s, Stephen King was officially a household name. Writer of such instantly memorable titles as “Carrie,” “The Shining” and “The Stand,” it was very unlikely to find someone who’d not read – or at least heard of – a Stephen King novel. The author was getting so big that pretty much anything he published landed on the number one spot of the bestseller list. But would his devoted readers gobble up anything he put in front of them? That was put to the test in the middle of 1982, when King convinced his publisher to put out a collection of four novellas he’d written in between novels. The stories had some macabre elements in them, and one did indeed feature a bit of the old supernatural, but for the most part these stories were dramas that dealt with the human condition. The collection was called “Different Seasons,” and while it wasn’t a hit on the same level as his previous books, it sold well enough to keep King’s name in the spotlight. More than that, however, it proved that the author could write more than just horror.

One of the stories in “Different Seasons” is “The Body,” a story inspired by bits and pieces of King’s memories as a teenager growing up in a blue collar household in the 1950s. Ultimately, King produced a tale about four kids in their early teens who embark on a trip into the deep woods to find the dead body of a young man supposedly hit by a train. During that brief two-day journey, they discover much about themselves and lose a sizable piece of their innocence. Not necessarily the obvious source material for a movie – let alone a great movie – but against all odds “The Body” would eventually become a classic of 80s cinema, a movie people of a certain age have seen countless times and can quote without effort. How did it all come together ? We’re going to find out just what happened to Stand By Me.

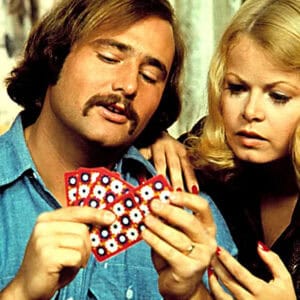

The saga begins in 1983, when writers Raynold Gideon and Bruce A. Evans both fell in love with King’s novella. Seeking to secure the rights, they contacted King’s agent, who promptly told them King wanted 100 grand for the the story and 10 percent of the gross of the finished movie – needless to say, a whole lot of money, especially for a project that would not have any bankable stars in the lead roles. Gideon thought to attach a hot director to the project to help get it off the ground, and he just so happened to be friends with one: Adrian Lyne, who was coming off the massive success of Flashdance. Lyne liked the story, and with him tentatively on board, Evans and Gideon went off for eight weeks to write the screenplay, while independent company Embassy Pictures was allegedly the only studio in town even remotely interested in producing this unusual coming-of-age tale.

One issue reared its head early on. Though he was intrigued in the project in theory, Adrian Lyne wanted to take a long vacation after making his follow-up to Flashdance, 9 1/2 Weeks. In fact, he wanted a very long vacation: six months. Gideon and Evans balked, knowing full well that they had to strike while the iron was even remotely hot. Lyne gave up the project to go on vacation, and “The Body” found itself in the hands of Rob Reiner.

The former All in the Family star had directed two pictures for Embassy, This is Spinal Tap and The Sure Thing, and before long he was on board to direct this, a very different kind of movie for him that he could still infuse with his notable comedic sensibilities.

Enthused as he was about the script, Reiner felt it needed some work. He couldn’t wrap his head around what exactly the issue was, until he realized that the script lacked focus. As was the case with King’s novella, the four boys were given equal weight in the screenplay, a traditional ensemble. Reiner was drawn to the character of Gordie Lachance, a burgeoning writer still traumatized by the death of his beloved older brother. Gordie feels lost in the world, especially in his own home, where he is basically persona non grata in the eyes of his judgmental father. Having grown up feeling lost in the shadow of his very famous father, the legendary comedian Carl Reiner, Rob felt a kinship with Gordie, which led to the character becoming the focal point of the narrative. The revised script was given the greenlight by Embassy and an $8 million budget.

Reiner was evidently meticulous when it came to crewing the film, taking personal interest in selecting stagehands, prop men, electricians, grips, the entire unit. Reiner’s reasoning was that, quote, “it takes only one jerk to ruin the attitudes and camaraderie of a movie company.”

Casting would have to be just as meticulous, obviously. Reiner knew that young men in the 11 to 14 age range couldn’t necessarily bring the kind of intense performances he’d need just from being great actors, so he intentionally chose actors who were close in personality to their respective characters. Supposedly Reiner auditioned at least 70 young actors, eventually landing on River Phoenix (fresh off Joe Dante’s Explorers) as the soulful de facto leader of the group, Chris; Will Wheaton as the haunted Gordie; Corey Feldman as rage-filled reprobate Teddy; and Jerry O’Connell, in his very first movie, as gullible goofball Vern.

To play Gordie’s deceased older brother Denny in flashbacks, Reiner called on his Sure Thing star John Cusack for a favor. And to play sadistic town bully Ace Merrill, Reiner cast Kiefer Sutherland, son of Hollywood royalty Donald, in one of his first major roles. Reiner felt Sutherland’s soft-spoken voice and calm demeanor would make Ace far more frightening than an actor who might go over-the-top with his performance.

Casting the adult Gordie, who is seen at the beginning and end of the film as well as serves as its narrator, was a challenge as well. Reiner first cast the actor David Dukes, but while recording his voice-overs Reiner found he didn’t think the actor’s voice was right. He then went to his This Is Spinal Tap star Michael McKean, but he didn’t quite work out either. Reiner eventually landed on Richard Dreyfuss, whom he’d known for years.

For two weeks before production began, Reiner and his four leads went to Oregon where filming would take place to engage in a bonding experience, playing theater games and trust exercises which would better acquaint the boys with one another. There was also much rehearsal, as the dialogue was complex – and in some cases, profane – and Reiner wanted to ensure that his young leads would be ready to go as soon as principal photography began. Reiner would later say that after the two weeks of hanging out the four-kid unit was a well-oiled machine.

And that almost did not happen. Literally two days before filming was to begin, the production got word that their studio, Embassy, had just been sold to Coca Cola, which promptly shut the movie down. The cast and crew didn’t know if they were going to have to drop everything and head home, but they found themselves rescued by a legend in the business: Norman Lear. Lear was the previous owner of Embassy before it was acquired by the soda company, and because he still believed in Stand By Me, he put up the necessary $8 million out of his own pocket. It probably didn’t hurt that Lear was the creator and producer of All in the Family back in the day, hence he knew that show’s lovable “Meathead” Rob Reiner very well.

Back on track, the production would take approximately two months to shoot. As was the case with the characters in the story, the boys would grow up fast in real life. For Feldman, it was his first time shooting a movie without his parents around, freeing him up to do whatever he wanted and let out some of the aggression that had built up inside him. He and River Phoenix, who had a similarly troubled relationship with his parents, would wander off into town after shooting and hang out with the local teens, and the two young men quickly discovered the allure of beer and marijuana. Sadly, this might be considered where both actors would begin a long road of addiction that only one of them would eventually conquer…

Feldman was apparently a bit of a bully on set, once getting into a very real fight with Wheaton. One day Reiner had to pull him into his trailer and give him an extended talking-to, after which Feldman put himself on a more professional path.

Wil Wheaton, on the other hand, was a very good boy indeed, as his mother was never far away – she’s even an extra in the infamous pie-eating contest sequence. Speaking of that scene, Reiner later considered cutting it from the film, as he worried it was too silly and out of sorts with the rest of the picture, but everyone who saw the sequence loved it and it would get such big laughs at screenings that he decided to keep it in, calling it a “giant splash of color” in an otherwise gentle tone poem.

A very notable experience for Phoenix happened at one point: he lost his virginity at the tender age of 15. Even more eye-opening, he lost it with a family friend and had his parents’ blessing beforehand, the experience taking place in a ceremonial tent somewhere in the Oregon woods. Feldman later said when Phoenix came back from that excursion, he was a changed man. Understandably.

While the young actors were naturally talented, Reiner would sometimes have to coax a little extra out of them. The scene where Chris laments being unfairly blamed for stealing money at school even though a teacher was responsible is one of the most moving in the film, though Reiner had to get Phoenix to truly break down believably. Before shooting, Reiner instructed the young actor to think of a time when an adult had really let him down. That struck a nerve, because Phoenix absolutely crushed the heartbreaking moment, although he never revealed what memory he used to help get him there. Incidentally, the scene was not in the original script; Reiner wrote it in a hotel room and cried to himself while doing it. And while the campfire sequence might look as though it’s really taking place in the woods at night, the entire thing was shot inside of a warehouse dressed up to look like it was the great outdoors.

Another of the movie’s most famous scenes involves the boys fleeing an oncoming train on a trestle bridge. While it looks for all the world like the train is bearing down on them, it was in fact very far away. The effect was achieved by using an extremely long lens – Reiner claims it was a 600mm lens – making it appear like the train is mere yards away from them. Here too Reiner needed to nudge his actors into giving a bit more than they were. Wheaton and O’Connell just weren’t convincingly scared-looking, and take after take disappointed Reiner. Finally, he yelled at the two kids, claiming they were wearing out the crew and wasting everybody’s time. Genuinely shocked, Wheaton and O’Connell quite believably screamed and cried during the next take, which is what wound up in the film. As soon as he called cut, Reiner hugged the two boys, who were both still bawling their eyes out.

Yet another notorious sequence sees the foursome fall into a pond, subsequently finding themselves covered with leeches. This was based on something that had happened to King when he was a teen. The pond was man-made, a giant hole dug in the middle of the forest and filled with water before principal photography. That said, by the time they actually got around to shooting the scene, it had become quite a disgusting body of water, mucky and bug-filled – for all intents and purposes, it had become the grotesque pond the characters sloshed around in. The leeches, on the other hand, were realistic props.

After photography had wrapped and the film started coming together, there was still the matter of distributing it. Remember, this was an indie made without a studio behind it. Reiner and company found a champion in the form of Michael Ovitz, the infamous then-head of Creative Artists Agency. Ovitz loved the film, but couldn’t get anyone to agree to distribute it. Finally, he forced it upon Columbia Pictures’ head Guy McElwaine, who initially had no interest, but when the exec screened it in his home with his kids in attendance, his attitude changed when he saw how much they loved it. He ultimately ended up taking the picture on and put Columbia’s full marketing force behind it.

An equally important screening took place for the man who created “The Body” to begin with, Stephen King. Reiner held a private screening for the author, and after it was over King seemed visibly moved, allegedly excused himself for 15 minutes. Soon after, he approached Reiner and told him it was the best movie made based on one of this works. King admitted to Reiner that Gordie was based on himself, and the best friend who inspired him to become a writer actually did die as a young man. To this day King maintains that Stand By Me is one of the best adaptations of his books, another of course being The Shawshank Redemption, which also came from “Different Seasons.”

At some point along the way, the title of the film changed from “The Body” to Stand By Me, inspired by the unforgettable Ben E. King song. Reiner thought if people saw a movie based on a story by Stephen King called “The Body” they’d just assume it was a horror flick. The song was crucial to the film and ended up enjoying newfound success after the film’s release. In fact, they even made a music video for it, and the song ended up in the Top Ten of the pop charts some 25 years after it was originally produced. Interestingly, Reiner had considered hiring Michael Jackson to do an updated version of the song for the end credits, even screening the film for the pop star, but he wisely decided to stick with the original.

Stand By Me was released in August of 1986, a year after shooting wrapped. Initially a limited release for two weeks, the film went wide on August 22nd and shot up to the #2 spot, right behind The Fly. The following week it was #1, and good word-of-mouth kept it in the top five until mid-October. It eventually ended up making $52 million domestic off an $8 million budget, and found further success on home video and cable, where it became a hugely influential movie for an entire generation of up-and-coming movie buffs.

Over 35 years later, Stand By Me has lost none of its power. Alternately heartwarming and heartbreaking, its authentic spirit and inherent good-nature ensure it will remain a go-to movie for those of us who consider it an integral part of our coming-of-age. Like a good friend, it will always be there when you need it. And it won’t even give you two for flinching.

Follow the JOBLO MOVIE NETWORK

Follow us on YOUTUBE

Follow ARROW IN THE HEAD

Follow AITH on YOUTUBE