Last Updated on June 27, 2024

Even the best filmmakers in history take big, ambitious swings and completely miss the mark at times. In the case of Brian De Palma – the supremely talented New Hollywood director behind such all-time great classics as Carrie, Dressed to Kill, Blow Out, Scarface, The Untouchables, Carlito’s Way, and more – many consider his most glaring cinematic blemish to be tone deaf adaptation of The Bonfire of the Vanities in 1990. However, if general moviegoers and De Palma fans knew about the crushing production woes relating to the ending of his uneven 1998 crime thriller Snake Eyes, perhaps they’d reassess their opinion.

Indeed, the original ending of Snake Eyes is so drastically different than what transpires at the end of the theatrical cut that it’s nearly impossible to judge the movie’s intentional merits versus the final product. Of course, the grand irony about the brutally botched ending of Snake Eyes is that most people only remember the captivating opening of the film, which features a hypnotic 20-minute Steadicam shot, as only De Palma could orchestrate.

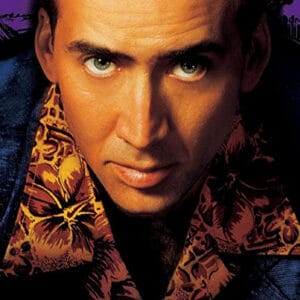

Although the sweeping Steadicam opener largely remains beyond reproach in 2024, the real question becomes: What happened to the ending of Snake Eyes? What was the original conclusion meant to be and why was it so dramatically altered to the point of requiring reshoots and a completely overhauled ending? It’s also worth wondering if the altered ending affected the movie’s critical reception and commercial performance at the box office. After all, De Palma was still hot from Mission: Impossible (which was co-written by Snake Eyes writer David Koepp), and Nicolas Cage was still fresh off his Academy Award win for Leaving Las Vegas. So what the hell went wrong? Well, from the breathtaking beginning to the head-scratching ending and everything worth exploring in between – it’s time to hit the felt, roll the dice, and figure out once and for all – What Happened to Brian De Palma’s Snake Eyes!?!

The first thing about Snake Eyes worth discussing relates to casting. While Nicolas Cage was always intended to play Atlantic City Police Detective Rick Santoro, the role of Commander Kevin Dunn, played by Gary Sinise, was originally offered to Al Pacino. Of course, De Palma and Pacino made cinematic history together in Scarface in 1983 and Carlito’s Way in 1993. However, Pacino turned down the role of Commander Dunne. The part was then offered to Will Smith, who agreed to star opposite Nicolas Cage in the film. However, when Smith asked for $12 million to star as the second lead, Paramount Pictures declined to pay such a hefty fee and Gary Sinise was cast instead. Smith would go on to star in Tony Scott’s Enemy of the State, another political thriller centered on the assassination of a high-ranking government official.

Now here’s a funny casting aside. While Sinise’s character is named Commander Kevin Dunne in Snake Eyes, the real actor Kevin Dunn also appears in the movie as the pay-per-view announcer Lou Logan. The identical names caused massive confusion on the set of Snake Eyes. At one point, the actor Kevin Dunn was put up in a glitzy penthouse suite in a luxury hotel while filming. When the production team realized they had accidentally given Gary Sisnise’s hotel to Kevin Dunn mistaking him for his character’s name, Kevin Dunn was forced to leave the penthouse and was sent to a modest chain hotel room where he stayed for the remainder of the shoot. Oh, the first-world problems of well-paid Hollywood actors!

Speaking of the film shoot, principal photography for Snake Eyes began on August 4, 1997, and was completed on November 2, 1997. Although principal photography wrapped two weeks ahead of schedule, reshoots were required to film a new ending. The three-month filming schedule was divided between Atlantic City, New Jersey, and Montreal, Canada locations. Believe it or not, only two weeks were spent on location in Atlantic City and Egg Harbor Township in New Jersey, with most of the footage capturing interior and exterior shots at the Trump Taj Mahal Hotel & Casino. John Heard, the actor who plays the Millennium Powell Casino owner and director Gilbert Powell in Snake Eyes, is directly modeled after Donald Trump. With only two weeks spent on location in Atlantic City where the story takes place, the rest of Snake Eyes was filmed entirely on studio sets and soundstages in Montreal. The Montreal Forum hockey stadium was also utilized for interior shots of the Casino depicted in the movie.

Now, it’s impossible to talk about Snake Eyes without mentioning the tour-de-force Steadicam shot that appears to be a single, unbroken 20-minute take. First off, the shot was filmed by top-tier Steadicam operator Larry McConkey, the same man responsible for the iconic Steadicam shot through the Copacabana nightclub in Goodfellas, among others. For Snake Eyes, the complex choreography of the Steadicam sequence begins with Santoro’s perspective before shifting to the viewpoints of heavyweight boxer Lincoln Tyler, Commander Dunne, Julia Costello, back to Santoro, and finally, an omniscient God’s eye view from above.

While De Palma has made a living out of unparalleled tracking shots, split screens, and unbroken takes throughout his decorated career, the opening sequence in Snake Eyes features at least eight hidden edits to make it appear as if it’s one continuous shot. Most hidden edits come during the rapid whip pans across the arena during the sequence. However, reports claim that at least 12 minutes of the 20-minute opener were filmed in one single take.

Even with the covert cuts buried in the sequence, the opening of Snake Eyes remains one of the most ambitious, well-executed, and impressive single-take shots in cinematic history. It’s right up there with the opening shot of Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil and that unforgettable tracking shot in Alfonso Cuaron’s Children of Men. Not just from a technical standpoint, but thematically as well. The kinetic movement of the opening sequence in Snake Eyes establishes the camera as a vital character in the movie, an unreliable one that cannot be trusted to tell the unfiltered truth at any given moment during the story. Although it’s easy to read Snake Eyes as a reference to the cold-blooded Commander Dunn and Gary Sinise’s beady reptilian pupils, the title of the film also alludes to how the camera slinks, snakes, and slides through the Casino in a serpentine fashion throughout the movie to provide a grand spectacle.

Interestingly enough, in real life, snake eyes lack eyelids and remain open at all times, somewhat similar to the visual effect created continuous Steadicam shot the movie opens with. Moreover, instead of having eyelids, snakes protect their vision through a specialized scale known as “a spectacle.” Therefore, the camera in the movie functions as Snake Eyes, with De Palma using all of his cinematic tricks to enhance the spectacular effect. As for the shifts in perspective and the repetition of events seen from different points of view, it’s no surprise that De Palma cited Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon as having a major influence on Snake Eyes.

Okay, now it’s time to address the elephant in the room. The original ending of Snake Eyes was meant to feature a massive tidal wave that destroys the Atlantic City Boardwalk and floods the Millennium Powell Casino, causing even more chaos and pandemonium as Santoro chases down Dunne through the submerged wreckage. In the original ending, Dunne is killed by the tidal wave rather than commit suicide as seen in the theatrical cut. The tidal wave results from Hurricane Jezebel, the tropical storm mentioned throughout the movie, beginning with lighting strikes heard as the Paramount logo first appears. The climactic tidal wave was an expensive FX-driven spectacle created by Industrial Light & Magic. All the references to Hurricane Jezebel in the movie were meant to slowly build momentum for the tidal wave to deliver a devastating knockout punch in the third act.

According to De Palma in the Noah Baumbach and Jake Paltrow documentary of the same name:

“My concept was, when you’re dealing with such corruption, you need God to come down and blow it all away. It’s the only way. It’s the only thing that works. That was the whole idea of the wave.”

Sadly, Paramount did not support the idea, with De Palma adding:

“And nobody thought it worked. So we came up with something else, which I never particularly thought worked as well as the original idea.”

It’s interesting how De Palma evokes God and the notion of a deus ex machina in his conceptual idea. Cutting the original ending of Snake Eyes robs the movie of its deliberate Biblical subtext, a thematic throughline that often goes unnoticed in the movie. Note how the name Santoro translates in Latin as Saint or someone born on All Saints Day. Santoro and Dunne also went to the same high school in Atlantic City, where Sea Devils are the school mascot. The tidal wave meant to destroy the boardwalk and casino in the original ending can be read as a kind of Sea Devil.

Meanwhile, Hurricane Jezebel is named after the Biblical siren who seduced the Saints into idolatry and sexual immorality, something Santoro grapples with in the movie. Santoro idolizes Dunne and his status as a Navy Commander and cheats on his wife and girlfriend with his mistress, Julia. The tidal wave at the end was meant to wash Santoro’s soul clean as a kind of spiritual ablution while ridding the city of its foul corruption.

Alas, when Paramount screened the original ending to test audiences, it was received so poorly that the studio demanded De Palma reshoot a new ending. De Palma came up with the idea to have Dunne fatally shoot himself in the chest after being cornered by authorities. The movie then picks up the original ending, which features the heartfelt discussion between Santoro and Julia on the boardwalk. Even so, several references to the original tidal wave ending can be seen and heard throughout the movie. For instance, the movie opens with a reporter in the rain outside the Casino addressing the tropical storm. Then, around the 36-minute mark, Lincoln Tyler says to Santoro: “You hear that storm out there? I wish it would blow this whole town away,” directly foreshadowing the originally conceived ending.

Later, an ambulance rushing down the coast to the casino during the finale is nearly hit by a massive tidal wave before the shot abruptly cuts away. During their boardwalk discussion, Santoro also mentions to Julia how all he can dream about is being underwater in the tunnel below the casino and how he drowns this time. Without the tidal wave ending, this dialog makes zero sense. The point is, that so much planning went into the climactic tidal wave that even when the original ending was removed, vestiges of the wave can still be felt, seen, and heard throughout the movie.

Speaking of the painstaking tidal wave planning, ILM visual FX supervisors Eric Brevig and Ed Hirsh were put in charge of the ambitious spectacle. The two leaned on their experience creating FX for Paramount’s Twister two years prior and were put in charge of depicting the tidal wave breaking, crashing into the Atlantic City boardwalk, and producing tons of seafoam as a result. According to ILM FX artist Habib Zargarpour, the computer-generated tidal wave was designed and animated to break in a controlled manner and then shaded with fractal composites. The challenge was to avoid making the CGI wave appear like dirt and dust and more like natural water. According to Zargarpour:

“The key was in pRender, the particle-rendering we had for Twister, where you could cheat the size of the particle from the light POV, from each light. So, the trick for making them look like water was to take the key light, or backlight, and make the particles look really small from that light’s point of view. That made the light go through and scatter. Otherwise, it’s going to look like chunky ice cream.”

Miniature models and 3D blueprints were utilized to capture the crashing tidal wave. The miniatures were used to create splashing effects, while the 3D models were used to depict the pier and boardwalk. Yet, despite all the time, money, and effort spent on the showstopping finale, it all went for naught thanks to a tepid response from a fickle test audience. Even Steven Spielberg, who previewed a rough cut of Snake Eyes for his old friend De Palma for the last time, was unable to convince the powers that be to retain the original vision for the pulse-pounding pinnacle. The reshot ending completely alters the tone and tenor of the movie’s primary intention and completely robs moviegoers of the Biblical underpinnings the movie was conceptually founded on.

Despite Paramount’s unwise decision to compromise De Palma’s vision, the original tidal wave ending of Snake Eyes can be seen on YouTube. The epic FX-driven sequence lasts much longer than the ending featured in the final cut and depicts the tidal wave crashing into the Millennium Powell Arena and knocking Dunne to the floor as Sontoro and Julia take cover. The giant metallic orb that serves as the logo for the Arena rolls into the casino and crushes Dunne to a pulp, leaving the storage area of the arena submerged in several feet of water. Dunne getting destroyed by the insignia of his corrupt co-conspirator would have added a delicious slice of poetic justice to the ending of Snake Eyes. Alas, as it is now and forever, Dunne’s awkwardly filmed, tacked-on suicide is far less satisfying and feels like a cheap and rushed last-minute addition that benefits nobody. The lesson learned? Never make creative decisions based on the response of a fickle test audience, especially for a movie directed by such a tried and true artist like Brian De Palma.

Although Snake Eyes turned its pricey $73 million budget into a $103 million global moneymaker, the movie lost money at the domestic box office. Snake Eyes grossed just $55 million in North America, a disappointing haul for Paramount and De Palma after their runaway financial success with Mission: Impossible two years earlier. Yet, looking back at Snake Eyes in 2024, it’s easy to ascribe the critical and financial failure of the movie to the abandonment of the climactic tidal wave spectacle. By witnessing the originally filmed ending online, it’s clear that De Palma’s intention for concluding Snake Eyes works much better than what is ultimately presented to viewers in the theatrical cut. At the time, the film drew criticism for revealing the killer too soon, something De Palma took umbrage with, telling documentary filmmaker Mark Cousins:

“There’s a lot of discussion in Snake Eyes about why we reveal who did it so soon. Well, the problem is that it isn’t about who did it. It’s a mystery about a relationship, two people, and how finding that out affects their relationship … those kinds of procedural movies are extremely boring…”

As for further criticism, much has been made about the dazzling Steadicam shot that opens the film and how the story tends to follow apart afterward. The irony is that the badly botched ending of the movie is what ultimately tells the story of Snake Eyes’ purgatorial fate. Although the movie as a whole is better than people remember it for and deserves to be recommended for De Palma fans, Snake Eyes could and should have functioned more dramatically had the original tidal wave ending remanded intact as a showstopping spectacle. That, dear friends, is more or less What Happened to Brian De Palma’s Snake Eyes!

Follow the JOBLO MOVIE NETWORK

Follow us on YOUTUBE

Follow ARROW IN THE HEAD

Follow AITH on YOUTUBE