Last Updated on August 2, 2021

Welcome to The Best Movie You NEVER Saw, a column dedicated to examining films that have flown under the radar or gained traction throughout the years, earning them a place as a cult classic or underrated gem that was either before it’s time and/or has aged like a fine wine.

This week, we’ll be looking at BUG.

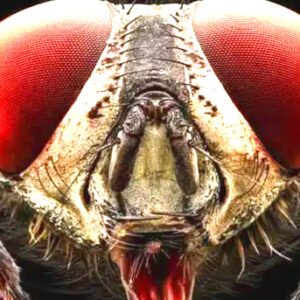

Unless the bugs are looking at us… listening to us… living in – ahem. Excuse me. BUG.

THE STORY: A haunted woman with a ex-husband in the clink and a traumatic past eating away at her encounters a disaffected young man who ushers her into an underworld of conspiracies about conspiracies, army experiments, aphids, microchips, the status quo, remote control assassins, and love. Crack, tinfoil, and pliers may or may not be involved. Tinfoil notably not in hat form.

THE PLAYERS: legendary director William Friedkin, back for his second guest spot on this column. Michael Shannon, Ashley Judd, Harry Connick Jr., Lynn Collins, Brian O'Byrne. Screenwriter Tracy Letts.

Also, bugs.

More bugs.

Even more.

Or none at all.

What makes a great film is a great script. You start with a great script, and then you go to a great cast. Now, a lot of the time, that doesn’t mean anything today, it’s the special effects, but what I’m interested in are the screenplay and that the actors transcend their roles or become inseparable from them. “The French Connection” is the only exception to the rule that you have to have a great script. We had no script for “The French Connection” but I knew the story and the guys who did the parts knew the story, they went out with these cops. Everything else I’ve done that’s worked even moderately starts with a great script. This is the vision of the writer, Tracy Letts, and I’m simply a vessel in which it passed. – William Friedkin

THE HISTORY: Welcome back Mr. Friedkin, and thank you for consistently applying your passion and style to whatever the hell you want whether the studios or mainstream taste and sensibilities like it or not. Which is the only way I suspect a gonzo piece of cinema such as this movie could ever hope to exist. But exist it does, and drips with a kind of dread I find myself squeamish just thinking about. It's a genuinely uncomfortable movie, and that's an absolute compliment. BUG began as a play of the same name that already starred Michael Shannon in the role of Peter and premiered at the Gale Theatre in London on September 20th, 1996. Its American premiere came after a series of revisions in Washington DC on March 18th, 2001 (often the case in theatre as shows transfer after a first round or two of what is basically public workshopping). The Off-Broadway premiere came three years later, which is where and when Friedkin felt the first sparks of the show's ferocious passion sear his heart. Less than two years later, he was making the movie.

Filming took place in chronological order over just twenty one days, with the last being a day of reshoots due to a fire on the set. "There’s often a fire on the set that I film on," said Friedkin. "It’s not intentional, but sometimes things go wrong." First seen at Cannes in 2006, BUG was released in cinemas on May 25th, 2007 and went on to gross a worldwide total of $8 million.

When my agent sent to me the script, she said to me that I may not want to go there. Immediately, that intrigued me. I don’t think that she was intentionally using reverse psychology, but that was the effect that it had. I became willing to take on the part before I had, in fact, read it. There’s a part of me that gets really competitive with my own creativity. I was always attracted to very intense [roles] as a child. In fact, when I was little, I wanted to grow up and be intense. I thought that the characters [in Bug] were very real, grounded and clearly wounded with a lot of dark secrets that they feel compelled to protect.

– Ashley Judd

WHY IT’S GREAT: When I first encountered a poster for BUG in the wild (specifically this one), the image – from the color and quality of the skin to the composition to the insertion of the title – left me simultaneously attracted and repulsed. Unsure of myself, afraid to take the chance, I went away. It was only later when I first began braving the further reaches of cinema on my own that I re-enountered BUG, and finally took a chance on expanding my storytelling horizons. But it's far from a horror picture alone, and maybe not even really that, as Friedkin himself describes: "It’s not a genre film, but marketing works in mysterious ways. They have to find a genre for it. 'This is a comedy. This is a melodrama. This is a love story. This is a horror film. This is an adventure film.' Bug doesn’t fit easily into any of those categories." And that's a big part of its beauty to me. You have this film – this scratched piece of celluloid chronicle the lives of two lost humans who find each other in the hot, empty, sticky hell of Oklahoma – and it's as disturbing as it is sweet, as keenly insightful as it is sleezily exploitative, as honest as it is shameless.

The film begins with a mysterious shot of the blue-hued hell that awaits at the end of this tinfoil-wrapped funhouse ride, before giving us a long shot approaching the motel in the middle of nowhere that the majority of the story’s action will take place. The faint whirr and chop of a helicopter’s blades can be heard underscoring the approach, sounds that may be real or they may be imagined and either way you’re going to hear them again and again whether you believe in them or not. And that right there is part of the great thrill and fun of this film – Letts, Friedkin, or even both could have agreed to make things easy on the audience. They could have woven in little clues to help the most astute of viewers deduce once and for all an answer to the ever-present question of “what is real.” They could have made sure certain cues only appeared at certain times and with certain set-ups, that some character would accidentally slip up and let loose the truth.

Except, to mix my movie metaphors: for this sticky dish, there is no spoon. Reality, truth, past, history, future possibility – all are mutable. All are malleable. None have an end, and nothing is absolute.

No, by and large, all of the fans of Bug I have encountered for the play and the film have been pretty straight up, just normal people. I think people who were truly paranoid couldn’t watch it, or maybe would be afraid to see it. Or maybe it wouldn’t live up to their own hallucinations. I don’t know. I made a conscious choice once I did the movie—I had performed Bug over 200 times on stage; I did it in London, I did it in Chicago, and I did it here in New York. And there was actually a production going on in L.A. and they called me, and I said no, I said I was all Petered Evans’d out. It was a tough role, because when I was doing the play version, we would do it eight times a week, sometimes twice a day. I love that character to death, but man, it was intense. – Michael Shannon

Friedkin could also have had fewer crack pipes and joints and bottles, but that too would be a lie. Those things are part of the lives of these people, and the use and abuse of those substances speaks volumes about every character while hinting volumes about human experience of the world. This is a fable of the damaged and the self-destroyed, souls that have worn themselves ragged running barefoot on the glass-strewn road of recovery, running until their lungs burst away from fear and loss and mistakes and the inevitable, potentially-crippling aches and schisms that can come with opening your heart to another human being.

We re-watch movies for any number of reasons. Maybe we want to recapture what it was like seeing it for the first time, maybe we want to show it to a friend or a partner or a parent, or maybe we are just in the mood for that particular story. BUG you should re-watch for the skillful cinematic storytelling, the embellishes of ambiguity, and the tiny touches that constantly tip the characters closer and closer to their respective fates. One of the first shots is of the hotel room’s night table, and its one which immediately presents us with a portrait of addiction. Drugs, drink, and a telephone. A telephone that keeps ringing and ringing, constantly reminding Agnes (Judd) of her connections to the outside world. To what is, ostensibly, “reality.” And curiously, for all the ways its presence seems to torture her, she doesn’t disconnect it. That phone and the tether to reality and the world it represents are her sole hold on sanity… until the arrival of Peter (Shannon).

I guess movies are harder to shock people with; we’ve pretty much given them everything we can give them. There’s something about the visceral experience of seeing live performers that movies will never be able to capture, but then you also can’t exactly build huge oil derricks in the theatre either, so they’re just two different experiences. I think people are more willing to go to live theatre not knowing what they’re going to see. We don’t do that with movies. – Tracy Letts

As the telephone is to Agnes so to are bugs to Peter, and so to do they in time become for her as the phone’s power is eclipsed in the face of who Peter is and what he can be for her. And a re-watch of BUG reveals even more starkly how every time either of these two characters opens up to the other, whether that opening be an offhand remark or a sexual encounter or a wrenching confession, they also allow a little more of their psychosis into the space and the other person’s sight. Which is the eternal fear and danger, isn’t it? That by opening to the sun we might also let slip in the shadow. That by revealing ourselves, we’ll reveal the beast. Of course, what is the beast really? The beast is us at our most base, our most honest, our most emotional, our most primally alive. And seemingly by the end of the movie Peter and Agnes have, as David Milch articualted so well (admittedly about two of his Deadwood characters), both found someone they can be “pure in their insanity with.” And there’s a twisted sort of poetry in that.

Of course, none of that would make a lick of difference without a stellar ensemble to fill the skins of these characters. Characters who are at once nuanced and larger than life, who wrestle with titanic storms of emotion and experience as they fight keep themselves from being torn apart. Or from tearing others apart, for that matter. Or who allow the damage to become collateral because they can’t bear to be lost alone. Whatever the case, as BUG oozed on I was reminded of something David Mamet once said: “Actors used to be buried at a crossroads with a stake through the heart. Those people's performances so troubled the onlookers that they feared their ghosts. An awesome compliment. Those players moved the audience not such that they were admitted to a graduate school, or received a complimentary review, but such that the audience feared for their soul. Now that seems to me something to aim for."

What attracts people to art in any form? There are a number of dark works that are intriguing because they reveal the constant struggle of good and evil that exists in all of us. I’m not just talking about where a guy takes a chainsaw and cuts somebody up for two hours and then the movie’s over. What you refer to as the dark side, I refer to as if it does have validity underneath the surface, it’s something that’s dealing with the thin line between good and evil that is in all of us. The character who seems to be the darkest at first, her ex-husband, is the guy that’s trying to save her. A lot of people don’t think about that aspect of it, but that’s what attracted me to this, aside from the great writing and the good roles. – William Friedkin

Ashley Judd (HEAT, DE-LOVELY, DIVERGENT) turns in stellar work, crafting a performance subtly shifts through unsettling phases in a transition from a person traumatized by loss and abuse (both self and other-inflicted), a person who is doing all they consciously can to drown herself in Lethe, to someone who would burn the world so long as she believed she wasn’t alone. Harry Connick Jr. (BASIC, INDEPENDENCE DAY) plays his part superbly, every bit the emotional manipulator and physical threat that preceding dialogue and character reactions had built him up to be. Lynn Collins (JOHN CARTER, THE MERCHANT OF VENICE) has to play the straight lady (so to speak) to the increasingly disturbing events around her, but approaches the part with an honesty and a passion that reflects for us, in the friendship she crafts with Judd, everything Agnes once was. Lastly, Brian F. O’Byrne (BEFORE THE DEVIL KNOWS YOU’RE DEAD, THE NEW WORLD) does wonders with his bit part as he loosens the last screws that anchor reality to the diving line between it and delusion. Of course, we can’t talk about BUG without mentioning the alternately awkward, sweet, terrifying, possessed, and titanic Mr. Michael Shannon (TAKE SHELTER, MAN OF STEEL). By the time the film adaptation was released in 2006 – two years after the Off-Broadway premiere – Shannon had spent a decade living in the role and working it out in a rather rare and special way. And without going too far into paroxysms of praise, suffice it to say that he kills it. He presents a complete human being, one righteous and wronged and longing.

In life, no love is ever the same. No hope, no relationship, no heartfelt feeling is ever wholly like the last. So if love, like reality and truth, is mutable, is ever-evolving and infinite in its potential scope, then how do we know it? How do we recognize it in the dawn-filled fields or the shadow-choked alleys of our lives? BUG says we can, and we do, because there is a secret ember that remains at the heart of all possible permutations. We can and we do because, in the world of BUG, love is finding someone you want to walk hand and hand with into the dark.

And then make light with.

BEST SCENE:

BUG steadily builds and builds and builds as the barriers between self and other, truth and fantasy, outside and inside, possible and impossible are all broken down until that critical, insane, beautiful moment when Agnes finally wholly gives herself to the freedom she has finally found.

SEE IT:

You can buy BUG on DVD HERE!

PARTING SHOT:

It was the worst [marketing] campaign in the history of motion pictures [proclaiming BUG a hardcore horror film]. It was just an absolutely abysmally conceived and executed plan. When they first talked about opening the thing on 2000 screens, Bill and I both said, 'You’re crazy! Why would you do that? This is not that kind of movie, this is a small picture, you need to open this in New York and LA, and put it on the festival circuit to let it find its audience.' But they had this plan in mind to open on all these screens and con kids into thinking it was Saw or Hostel to bring them into the theater. As a result, people who would have enjoyed the film didn’t go see it, because they were put off by the marketing campaign, and kids who were enthusiastic to see the movie advertised were furious. 'Why are these people talking?' They didn’t understand that there would be these long scenes of dialogue, so they felt cheated. Because theywere cheated! I was very upset at the time– but you know, after a little time goes by, people don’t remember marketing campaigns. Eventually this movie will find its audience. And I think it has already started to– I‘ve started to hear from those people who see the thing on DVD and say, 'Wow, I don’t know how I missed this.' – Tracy Letts

Follow the JOBLO MOVIE NETWORK

Follow us on YOUTUBE

Follow ARROW IN THE HEAD

Follow AITH on YOUTUBE