Last Updated on August 2, 2021

Welcome to The Best Movie You NEVER Saw, a column dedicated to examining films that have flown under the radar or gained traction throughout the years, earning them a place as a cult classic or underrated gem that was either before it’s time and/or has aged like a fine wine.

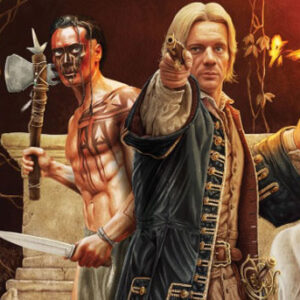

This week we’ll be looking at THE BROTHERHOOD OF THE WOLF.

THE STORY:

King Louis the XV sends a French knight and his Iroquois companion to the countryside on a mission to capture a beast rumored to have killed nearly one hundred people.

THE PLAYERS:

Writer/Director Christophe Gans. Actors Vincent Cassel, Monica Belluci, Mark Dacascos, Gaspard Ulliel, and Samuel Le Bihan.

Also, absurdly entertaining historical anachronisms.

THE HISTORY:

First off – in very recent history, one of the comments for my RAVENOUS entry was from MFC member Moat Man. It read, and I quote, "this plays well with Brotherhood of the Wolf for a double feature." Little did he know what I was already planning. Or maybe he knew exactly what I was already planning.

Whichever the case, here we are talking about one of the great DVD discoveries of 90s kids. French, sexy, bloody, with hints of horror, sin, indiscretion, and Something Serious to Say. Considering France’s history of Grand Guignol alongside its titular revolution, maybe it would be worth exploring more why the French do those all so well. But in the meantime: released in France in 2001 and the United States in 2002 (around the same year as THE COUNT OF MONTE CRISTO, THE MOTHMAN PROPHECIES, and ROLLERBALL), BROTHERHOOD OF THE WOLF made out much better than most of the movies we see in this column. As such, this entry is really more about championing BROTHERHOOD OF THE WOLF's rediscovery.

Encouragingly reviewed even at the time, theatrical release saw it gross over $70 million worldwide against a production budget of $29 million. From there, Universal paid $2 million for the domestic distribution rights andsaw it gross another $11 million against that. Since then, decent DVD sales and a Director’s Cut rerelease in 2008 have joined with its legacy to secure BROTHERHOOD OF THE WOLF a solid spot in the cinematic education of genre fans.

Fun fact: the website is still functional.

WHY IT’S GREAT:

You're not going to find many movies that are more deceptive yet honest than this one.

So on the one hand, the opening scenes are brave and bold in their complete commitment to establishing the tone. By the time the first rain fight has finished, we know there will be horror, we know it will tiptoe the line between monstrous and campy, we know there will be action set against beautiful landscapes, and we know the chaotic good nature of our pair of heroes. In just another scene or two we're introduced to the sex and the aristocracy (though the amount of sexy aristocracy is actually rather low), and the cards are laid bare for all the audience to see.

On the other hand, for all the blood, the action, the martial arts, the gunplay, the swordplay, the sexplay, the sex by itself, the rest of the sex, the sumptuous costumes, all of that stuff – the movie also has that elusive Something Serious to Say. And I'm not talking about the politics, except I'm kind of talking about the politics. Which leads us to a good question for any screenwriter to ask themselves when they finally get cracking on that new idea: why tell this story at this time? Or, to put it another way, "what makes this night different from all other nights?"

Based on a true story, or at least as much as about 90% of movies “based on a true story” can claim to be, BROTHERHOOD OF THE WOLF loosely adapts the book L’Innocence des Loups (The Innocence of the Wolves) by French zoologist Michael Louis and tells of a beast that terrorized the area of Gevaudan from the years 1764-1767. Reports place the number of people killed by it at nearly one hundred, with most of those being women and children, and while it is suspected that the Beast was killed… well, no one knows for sure.

What we do know is that the movie opens on the eve of the French Revolution, as an aging member of the aristocracy forgoes the chance to escape in favor of the chance to finish his memoir illuminating the truth behind that mystery. His story then becomes our bookend as we flash back twenty five years to Gevaudan itself, and the arrival of two strangers by King Louis XV himself – Mani, an Iroquois warrior, and his friend Gregoire de Fronsac, Knight and Royal Naturalist. Their mission is to capture, kill, and study the beast. Whatever they expect, what they find will be far more insidious. Because these are the final years before the Revolution, and a discontent that has simmered for centuries is about to spill over and burn the established way down to its bones and ashes. Which gives us an answer to our earlier question – this is a time of tumult and transition, where the blood tide is turning and people are questioning their position, their faith, and their fears. They are seeking justice and recompense. They are seeking the meaning behind the mysteries of their existence.

And what makes Gregoire the hero of the story is not that he’s a knight or that he’s a badass or that he’s smooth or that he’s looks like a French Jeremy Renner, but rather that he's enlightened.

"Actually, when [Christophe] got the script, the character of the Native American wasn't even in there. He wanted a character that kind of showed a different perspective of what was going on, and also a character that could express some of [his] own personal thoughts and feelings about life and culture and so forth." – Mark Dacascos

Early on we see a man run into the church, shouting about how his children have vanished and it must be due to him being damned an punished. Nobody disagrees with him, not his fellows of the same social status and certainly not anyone in the aristocracy. After all, as one of them says later on: “enough about this beast. It only devours vermin.” For ages and ages the commoners have believed they are vermin, those in power have believed the commoners are vermin, and everyone has agreed that vermin are really only good for one thing: working until they die. Whether that work be on the farm fields or the battlefields, the preservation of the mysteries of God and King are what has most mattered. The victims blame themselves, and in a society blindingly rife with injustices they can't conceive of another culprit.

But Gregoire comes in, complete with his brother from a very different mother, and after seeing a scene or two of physical sparring he takes the opportunity at dinner to do a little mental and verbal sparring of his own. In a fun bit of foreshadowing he presents a furry fish to the assembled aristocrats, something he says he found swimming in the waters of the New World. Many believe him, a few doubt, and one (Vincent Cassel’s Jean-Francois) sees through the taxidermied fabrication. Talk turns to the Church and the subject of deception, and Gregoire speaks one of the movie’s many great lines: “Lies may often appear as truths when they’re dressed in Latin.” Anyone who has seen this movie knows the parallels are clear here, the Church and the Established Order historically about to buckle under a madness caused by the self-created cankerous corruption that comes when those in power abandon compassion, thought, and dialogue. The moment serves to neatly set the rest of the story up while also serving as an important moment of experience in the journies of the characters.

And so we return to that earlier talk about honesty and deception, because the dinner scene shows us exactly what’s really going on in Gevaudan. The aristocracy, removed and gorging on the fruits of their people’s labors. Enlightenment, invited genteelly to sit at the table but not make too much of a fuss. The man-manufactured truth beneath a manipulated veneer of mystery and magic. The ongoing and thematically-infuesd battle of wits, skill, and purpose between Gregoire and Jean-Francois that will cost them and their closest companions dearly before the journey’s end.

"Brotherhood of the Wolf is a very important movie because it represents something new. The director Christophe Gans came up with the idea of taking a French legend and making it some kind of really strange, almost Chinese action movie. The result is something that I haven't seen anywhere before…. when Christian first came to see me, my character was just a regular bad guy – just bad, bad, bad – and I had to say no. But then the script was rewritten so he's secretly in love with his sister. For me, he's a victim, he's suffering more than anyone else in the movie, which is the best excuse for doing terrible things." – Vincent Cassell

Because, of course, the Beast is no beast. Or rather: the true beast is Jean-Francois, and Jean-Francois himself is the beastly product of a worldview that has warped over centuries. He's incestuous because the entire aristocratic system that came before him was incestuous. He's a violent rapist because he's the literal child of a system whose stranglehold on power is predicated on asserting dominance by any means necessary, morality be excused or damned. He trains an animal to hunt human beings and sends it out into the countryside because the Brotherhood he serves is the distilled poison of everything nasty about what came before, the final rivulet of puss, the bloody and rotten mouth that would rather figuratively cannibalize its fellow human beings than conceive of change. They believe the world is the Devil's playground, that the king has failed in his duty to enact God's will and preserve the system's purity, and that they need to save their way of life by, again, any means necessary.

Which brings us to the violence of their methods, and by proxy brings us back around to the subject of sex. Conventional wisdom dictates that all stories are, at their heart, about sex or death. Sometimes both. Definitely both in this case, with narrative developments and character choices merging together in passionate proof of that idea every time that which has been held in finally spills out. The Catholic Church is one predicated on repression, an internal smothering of dreams, fears, and desires that can lead to great wounding. Whether we're talking about the coming Revolution in a greater sense or Jean-Francois' personal twisting in a more specific sense, in BROTHERHOOD OF THE WOLF acts of violence so often follow suggestions of sex or expressions of desire precisely because those acts can serve as an outlet for such feelings. A purging, a destruction, a projection of corruption onto a source outside the psyche because that's simply something easier to bear.

But with the tightrope this movie walks between genres, set pieces, and social commentary, any director would need a cast of the highest caliber. And Christophe Gans has it here, his collection of actors able to deceive and believe in equal measure. Samuel Le Bihan is a strong lead in the classic style – suave, passionate, quick witted, and inquisitive. Mark Dacascos brings a fantastic grace to his fight scenes that stands well apart from the style of the strange world he wanders in, and the work he put in to crafting an accurate portrayal of the character's culture shows. As for Emilie Dequenne as Marianne, there's this saying about how Ginger Rodgers did everything Fred Astaire did, just backwards and in high heels. And that's about how she is in this, giving Le Bihan a run for his money with the complexity she carefully brings to the character. More than "strong" or "independent", she clearly plays her own games, takes charge of her own mind and heart, and is as intensely adept at handling herself as he is. Hamstrung somewhat by the construction of the story and her character's place in it, she nonetheless works with the sees of her matieral to craft something special.

But.

Fans of Vincent Cassel know that when it comes to any movie that he’s in, there is a decent chance he will be the standout element. It’s arguable whether his performance here proves the rule or birthed it, but either way Jean-Francois is a character begins as a deliciously smarmy bastard before convincingly journeying into his own heart of darkness to reveal the damaged, poisoned, destructive bastard of his history. One who, in his own disturbing way, knows himself for what he is. “I am a hunter,” he remarks to Gregoire, “and that passion has cost me dearly.” And whether we’re talking about his relationship with his sister or his relationship with other human beings, the truth of his tragedy is the same – he knows no other way of being. It’s why he is the complete, corrupted, personified coalescing of every antagonistic force and viewpoint in play in this time period, and it’s why he has to die by the story’s end.

After all, isn’t that what stories with horror and monsters do? We face our fears, our demons, our misdeeds – often we finally face ourselves – and the story leaves us with hope that we can survive the encounter. Sometimes, the cycle only spirals deeper and the victim becomes the monster themselves (see the French Revolution). But that doesn’t change what’s being said when BROTHERHOOD OF THE WOLF cuts to credits. And that doesn’t change the chance that change can still come, even after the beheadings and the burnings and the witch hunts and the ascendency of the new tyrants.

Because even after all that, one light remains for those who know the truth behind the mask:

The beast was defeated once. It can be again.

BEST SCENE:

I haven't touched much on the action, but there's some great action. As it really sells itself (and is more what this movie is known for), it seemed prudent to use this opportunity to talk about the other facets of this gem. But for those of you who haven't seen BROTHERHOOD OF THE WOLF yet, here's a taste in the form of the first hunt for the Beast.

SEE IT:

You can buy BROTHERHOOD OF THE WOLF on DVD HERE!

PARTING SHOT:

“As long as the general population is passive, apathetic, diverted to consumerism or hatred of the vulnerable, then the powerful can do as they please, and those who survive will be left to contemplate the outcome.” – Noam Chomsky

Follow the JOBLO MOVIE NETWORK

Follow us on YOUTUBE

Follow ARROW IN THE HEAD

Follow AITH on YOUTUBE