Last Updated on May 28, 2024

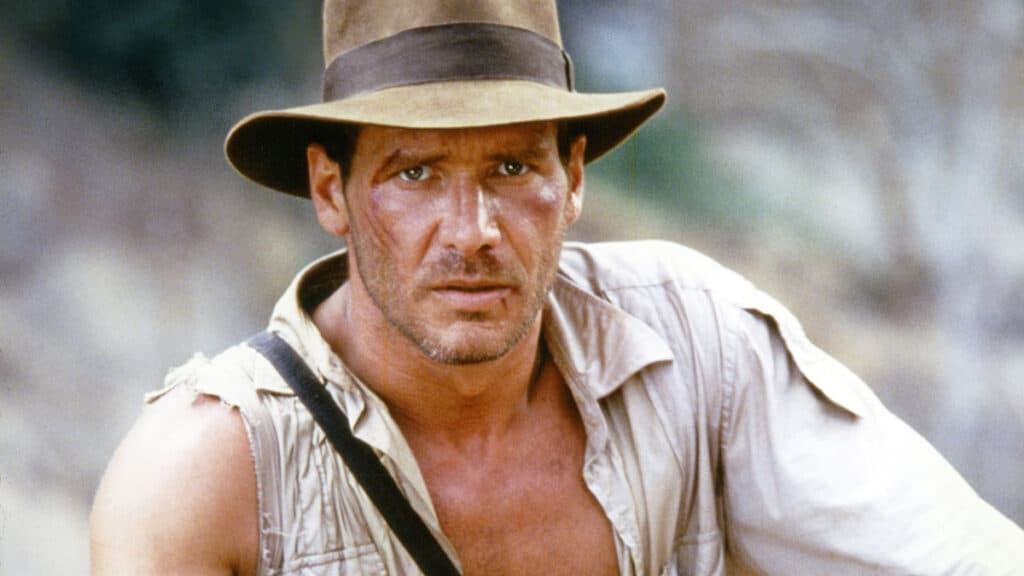

After foiling a Nazi plot to unleash the power of the Ark of the Covenant on the world, the intrepid archaeologist, Indiana Jones, is heading beneath the Pankot Palace in India to recover the mystical Sankara Stones from the evil Thuggee cult, led by the deranged priest Mola Ram. This mission is all in a day’s work for Dr. Henry Walton “Indiana” Jones Jr., whose heroism is becoming a legend worldwide after his thrilling adventure in Raiders of the Lost Ark. Grab your trusty braided kangaroo leather whip, bury your entomophobia deep, and bring your appetite for chilled monkey brains because we’re looking back on the second chapter of Lucasfilm’s Indiana Jones franchise, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. For those who may not be aware, this now 40 year old film was a lightning rod for controversy back in 1984, with it being one of the films responsible for the creation of the PG-13 rating at the MPAA (indeed, it’s easily the most violent PG movie ever made). So how did it come to be?

One of the first prequels

When executive producer and story writer George Lucas teamed up with Steven Spielberg for the Indiana Jones project, the creator of the Star Wars Universe said he’d imagined Indy’s journey as a trilogy. Believing in his friend and collaborator’s vision, Spielberg assumed there was a plan to carry Indy through a three-part adventure. Unfortunately, there was no such thing. Much like Indy when he’s in a tight spot, Lucas flew by the seat of his pants when drumming up ideas for the whip-wielding hero’s epic excursions into the unknown.

Acting as a prequel to 1981’s Raiders of the Lost Ark, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom finds Indy in 1935 before the Nazi threat goosestepped onto the scene. Temple is tonally darker than Raiders, featuring themes of slavery, cultism, dismemberment, and human sacrifice. When asked about Temple‘s volatile vibes, Lucas and Spielberg said the film’s mood is likely the result of them both experiencing relationship trauma. Lucas was going through a divorce with his ex-wife Marcia Griffin, while Spielberg was exiting his union with music executive Kathleen Carey. Both men were in a vulnerable place and chose the Temple of Doom project as a way to exorcise their inner demons.

Indiana Jones in China? Or Scotland?

Initially, Spielberg considered bringing Karen Allen’s Marion Ravenwood back for another adventure, with her fabled father, Abner Ravenwood, introduced as a part of the plot. Wanting to hit audiences with a rollicking setpiece from the jump, Spielberg and Lucas envisioned a motorcycle chase scene on the Great Wall of China, with story elements revolving around China’s mythological Monkey King from author Wu Cheng’en’s 16th Century novel Journey to the West. When China refused to allow filming at the legendary location, the duo returned to the drawing board.

When their first two ideas failed, Lucas composed a treatment that could take Indy and his companions to Scotland, where a haunted castle would invite the fedora-hatted hero into another spooky setting. However, Spielberg needed a break from the supernatural after co-writing Poltergeist and having Indy encounter phantoms during the Raiders of the Lost Ark finale. Ultimately, Dr. Jones escaped to India, where a murderous cult welcomes the reign of Kali, the consort of Shiva and goddess of time, change, death, and destruction.

After settling on a location for Indy’s next expedition, Lucas and Speilberg contacted Raiders of the Lost Ark co-writer Lawrence Kasdan to help write the new screenplay. Surprisingly, Kasdan wanted nothing to do with the project. After hearing about the film’s darker direction, Kasdan balked at the themes associated with Indy’s subsequent undertaking. Calling the pitch “ugly and mean-spirited,” Kasdan declined the invitation to send a cinematic icon into the Temple of Doom. Kasdan recognized that Lucas and Spielberg were channeling aspects of the stress brought on by their respective losses into the project and left them to it.

Once it became clear that Kasdan was uninterested, Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz picked up their pens. With an extensive background in cultural aspects of the film, the pair relished sending Ford’s rough-and-tumble character to India for a cult-related conflict. After hearing Lucas and Spielberg’s ideas for the story, Huyck and Katz cherry-picked elements of each, arriving at a plot that involved Indy retrieving a sacred relic from a power-hungry cult leader.

In Raiders of the Lost Ark, Indy recovered the Ark of the Covenant alongside Marion Ravenwood, a quick-witted, driven spitfire with a mean right hook. In the Temple of Doom, Kate Capshaw’s Willie Scott, a nightclub entertainer in over her head, joins Dr. Jones, alongside Ke Huy Quan’s Short Round, a Chinese orphan, pickpocket, and all-around MVP of the film. Lucas initially wanted a virginal young princess to be Indy’s companion throughout the prequel. However, that idea didn’t fit the James Bond-like mold of the Indiana Jones franchise.

Indy’s new friends

Instead, fans got Kate Capshaw’s Willie Scott, a divisive character, to say the least. While Scott embodies the blonde bombshell archetype, audiences and critics responded poorly to Capshaw’s character and performance. Spicy reviewers noted Scott’s shrill whining throughout the adventure, while others were disturbed by the character’s shallowness, cultural insensitivity, and cowardice in the face of danger. In the years since Temple‘s release, a section of fans have warmed to Capshaw’s performance. Still, comparisons to Karen Allen’s Marion Ravenwood haunted Willie’s every move, leaving her disadvantaged.

As for Ke Huy Quan, the Academy Award-winning actor stumbled into the role when Lucas and Spielberg held auditions at a school in Chinatown, Los Angeles. On that fateful day, Quan was helping his brother prepare for his audition when the film’s casting director asked if he wanted to read for the part. Quan enthusiastically agreed and received a callback the next day. One year later, Quan teamed up with Spielberg again for the coming-of-age adventure classic The Goonies. Quan plays Data in the beloved film, a young inventor of questionable skill but with the best intentions.

Gross out gags galore

Concerned that audiences would zone out while learning about the Thuggee cult, Huyck and Katz floated the idea of sending Indy on a tiger hunt. During the pursuit, audiences would learn about the cult through engaging dialogue and suspenseful scenes of Indy stalking the magnificent beast. When Spielberg said he didn’t plan to stay in India for as long as it would take to film the hunt, the team devised the stomach-churning dinner scene where Dr. Jones and his companions dine on insects, wriggling baby snakes, eyeball soup, and chilled monkey brains.

The Temple of Doom dinner party is one of the most iconic scenes in the Indiana Jones franchise. However, representatives of India did not take kindly to how the dinner depicted their culture and cuisine. The dishes served in the extreme scene do not represent Indian delicacies, nor does the film portray the people of India in a favorable light. Disgusted by Temple‘s treatment of its people, traditions, and methods of worship, censors in India instituted a temporary ban on the Indy prequel in theaters.

Filmmakers and cast members mostly waved the complaints aside. Collectively, they claimed the dinner scene was supposed to be a joke, suggesting the Indians were more intelligent than the Western interlopers by serving them the meal they expected from a foreign organization. Temple of Doom eventually hit shelves in India, but only after the movie made its way to home video.

Just like filming proved difficult for Raiders of the Lost Ark, shooting Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom was no exception. The Indian government denied the filmmakers permission to capture portions of the plot in North India unless Spielberg and his team agreed to a list of demands. In addition to saying the temple Spielberg wanted to film in was off-limits, the Indian government wanted to make drastic changes to the script. Indian officials were insulted by the film’s depiction of their people and culture and did not want specific cultural identifiers used throughout the story. When the Indian government asked for final cut approval of the project, Spielberg and his crew abandoned plans to film in the authentic locale.

Instead, Spielberg and his crew set up shop in Kandy, Sri Lanka, located in the Indian Ocean, just off the southeastern coast of India. After losing the desired filming locations in North India, the production required more props, sets, and additions to the new setting. This setback added to the film’s budget, which was already more than Raiders of the Lost Ark. Once filming in Sri Lanka wrapped, the crew relocated to Elstree Studios in Hertfordshire, England.

Suppose there’s another scene in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom that’s burned into our memories alongside the cultist dinner party. In that case, it’s the one where Indy, Short Round, and Willie Scott encounter a hallway filled with thousands of creepy, crawly insects. Before you ask, yes, the bugs in this scene were legit. No one knows how many insects Spielberg used in this iconic scene, but there are rough estimates.

Green Pest Services said the production team gathered roughly 30,000 beetles and 50,000 cockroaches, with countless stick bugs, phasmids, Harlequin, and Hercules beetles. Frustration arrived on the set while trying to film the intimidating number of insects because if there’s one thing bugs don’t like, it’s light. With spotlights stationed every few feet, the bugs skittered toward the darkest corners of the set every time Spielberg called for action. To combat the camera-shy pests, Spielberg used a dump truck to unload an untold amount of bugs onto the stage, quickly capturing the scene before the bugs could escape into the shadows. Disturbingly, cast and crew members say they’d find bugs in their clothes, hair, and shoes after a hard day’s work, giving them a wicked case of the heebie-jeebies long after cameras stopped rolling.

Harrison Ford’s serious back injury

Spielberg experienced other filming challenges throughout production, including compensating for one of Harrison Ford’s injuries. Adding to his list of misfortunes while playing Indiana Jones, Ford suffered a spinal disc herniation while performing a somersault during a fight scene in Pankot Palace. Recognizing the degree of pain his actor had endured, Spielberg brought a hospital bed to the set so Ford could rest between takes. Known for pushing through pain, Ford insisted on continuing the movie as planned. However, his injury was so severe Spielberg eventually shut down production so medics could take Ford to Centinela Hospital, where he could get proper care and rest.

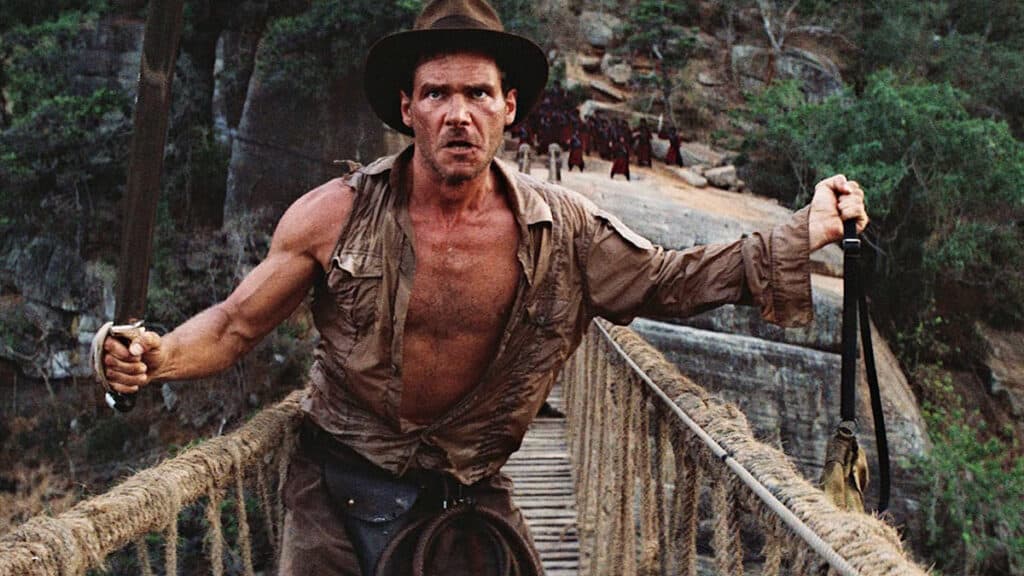

Despite experiencing setbacks, Spielberg finished Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom on time and within budget. He did film several pick-up shots after the initial wrap, which is commonplace throughout the industry. Despite its complicated setup, even the film’s thrilling mine cart sequence was a success. Constructed as a roller coaster and scale models with doll-like body doubles, the effects team used live footage and stop-motion animation to complete the scene. If you’re paying attention while watching the movie, you can spot the differences between the two filming methods. The mine cart sequence makes for one of the most exciting scenes in the film, and I find it baffling that no theme park has recreated the scene for an indoor roller coaster attraction. Whoever builds it could use John Williams’ rousing score to add authenticity and class to the experience.

The birth of the PG-13

In addition to being another jaw-dropping entry in the Indiana Jones film series, Temple of Doom helped make Hollywood history by being the first feature to introduce the PG-13 rating. Parents were shocked by the film’s contents, arguing that a PG rating did not warn about the prequel’s mature themes and gratuitous displays of violence. Meanwhile, neither Spielberg nor the studio wanted an R rating. As a compromise, Spielberg and MPAA president and rating creator, the late Jack Valenti, rallied for a rating between PG and R. A selection of executives disliked the idea, saying that checking IDs at theaters could become chaotic. However, many bigwigs agreed with the change, and the PG-13 rating was born. The rating system changed again in 1990 to include the “X” and “NC-17” ratings, but that’s for another video altogether.

Thankfully, everyone’s tireless efforts were rewarded when Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom hit the box office. The film earned an impressive $45.7 million in its first week, eventually climbing to $333.1 million worldwide. Lucas and Spielberg did it again, with crowds eagerly anticipating the arrival of Indy’s next odyssey. Come awards season, Temple of Doom won the Oscar for Best Visual Effects and the Best Special Visual Effects prize at the British Academy Film Awards.

While I prefer Raiders of the Lost Ark to Temple of Doom, Spielberg’s prequel is an entertaining exercise in producing a prequel that adds to an iconic character’s mythology and pushes the limits of what you can get away with while making a family film. Still, there’s plenty to love about Temple of Doom, from Ford’s dedicated performance to Ke Huy Quan’s boundless energy and loyalty as Short Round. Visually, the movie is another feather in Spielberg’s cap, with the film’s lavish costumes and locales standing out like the luminosity of charged Sankara Stones.

Despite everything, Temple of Doom presents a fascinating look into the psyches of two men using film as an outlet to process personal trauma. Indy’s adventure culminates into an outstanding third act that gives the adventurer some of his most extraordinary set pieces and defining character moments. Sequels often stumble under the weight of their predecessor. However, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom helped cement Indy’s place in pop culture, elevating the character to levels a franchise tastemaker of today can only hope to aspire to.

Follow the JOBLO MOVIE NETWORK

Follow us on YOUTUBE

Follow ARROW IN THE HEAD

Follow AITH on YOUTUBE