Last Updated on August 5, 2021

PLOT: The romantic entanglements of young Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin and famed poet Percy Shelley inspire perhaps the greatest horror story of all, Frankenstein: or the Modern Prometheus.

REVIEW: Five years after culling international acclaim for her debut feature WADJA, writer/director Haifaa Al-Mansour deserves the celebratory distinction of being the first Saudi woman to helm a Hollywood feature. However, the distinction might be a somewhat bittersweet one, as her new film MARY SHELLEY, despite another wondrously magnetic performance by Elle Fanning, ultimately registers as a bit of dodgy and stodgy affair. It’s dodgy because of its unscrupulous pardoning of Percy Shelley’s lecherous behavior; not just excusing it, but gratuitously accrediting it for more than it’s worth. And it’s a tad stodgy because, although the film has the lavish look and scaled weight of an epic period piece, despite the veracity of the story, it somehow hasn’t quite the substantive import. In the name of full transparency, this is not a horror movie. This is a biographical romance about the inspiration of a horror story. Heed this differentiation as you please, for your enjoyment might directly correlate with how well you manage expectations. Even still, as an outright Gothic romance, MARY SHELLEY is a well-meaning but sort of misguided horror origin tale.

Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin (Fanning) is an aspiring 16-year old writer living in bustling London with her sister Claire (Bel Powley) and famous philosophical scribe father William (Stephen Dillane). After writing a draft of a story that her father besmirches as the work of an imposter, Mary burns the pages and is sent off to Ireland. There she meets Percy Shelley (Douglas Booth), already a famed poet of the time. Percy courts Shelly almost instantly, despite later learning he’s a married man and father of a little girl. His wife Harriet (Ciara Charteris) harbors ill-will toward the romantically poetic wooer, and tries to exhort Mary of falling into the same trap she did. Upon feigning illness, Claire forces Mary to return to London. Percy follows along, intent on studying under William’s tutelage. When William learns of the courtship of his daughter and the subsequent infidelity of Percy to his wife, he throws the poet out on the street. Mary must make a choice: run away with the potentially unfaithful Percy and lose the love of her father, or stay home and lament her lovelorn heartbreak. The choice is made all the more difficult when the couple has a baby out of wedlock.

As Mary begins resenting Percy’s gallivanting dalliances, she becomes inspired to write a new story. When the couple attends a “Phantasmagoria” exhibit and witness a scientific reanimation process, another kernel of inspiration in Mary is struck. But it isn’t until Mary and Percy travel to Geneva and indulge in a bit of Bacchanalian debauchery with Lord Byron (Tom Sturridge), Claire’s newfound fling, that Mary is beset with such a profound sense of despair that she can’t help but begin scribbling the story what would ultimately amount to the 1818 volume, Frankenstein: Or The Modern Prometheus. The problem here is the movie gives too much credit to Percy as being the main inspiration behind the Mary’s masterwork. For all the neglect, abuse and abject pain Percy causes Mary (and Harriet) – aptly analogized as monstrous behavior in Frankenstein – it’s almost as if the movie suggests Mary owe him a debt of gratitude rather than the other way around. Percy’s a lecherous wretch, and no matter how inspirational his odious behavior proved to be, it cannot or should not be excused, much less lionized. To paint this historical truth with a romantic retrospective brushstroke, only serves to undermine Mary’s sole groundbreaking accomplishment. Mary and Mary alone deserves the credit, and despite their subsequent marriage after the book was published, Percy ought to hold more reprimanded blame.

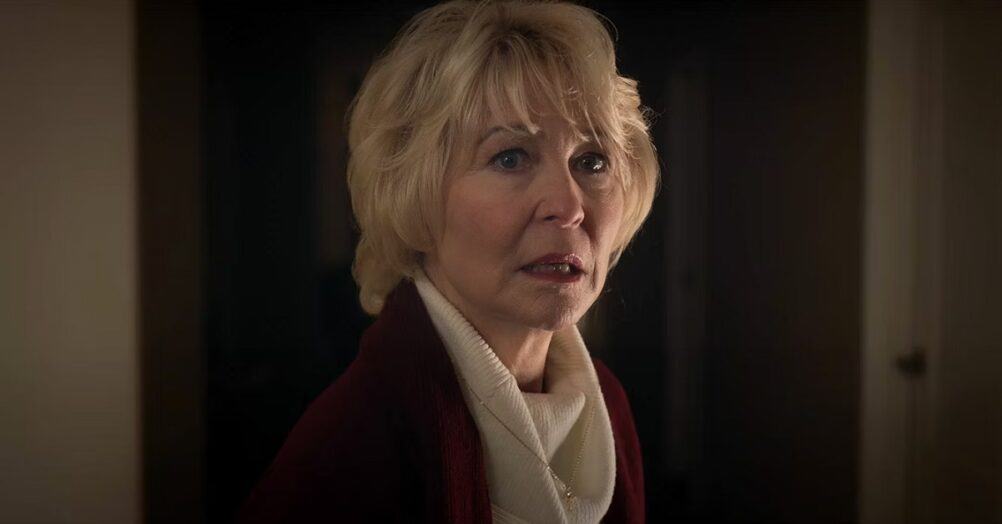

And yet, because of the rich epochal evocations, sumptuous cinematography, handsome costumes and sets, and one more compellingly emotive turn from Elle Fanning, the movie remains passably attractive throughout. Yes it runs a bit over its welcome, plodding at a leaden pace after the midway point, but the central performance by Fanning keeps the engagement focused enough. Fanning is impossible not to like, and improbable not to love. This goes a long way in forgiving some of the uneventful story beats and uninteresting plot turns, of which there are thankfully just a few. Also, because this is a movie about a novelist drafting a trailblazing tome, there’s a certain amount of frilly and florid dialogue that helps enliven the inaction. Even if there’s nothing enthralling to look at, there’s always something exciting to hear, whether it’s excerpts from Mary’s narration or daily conversation among 19th century artists. For a movie about an author laboring through the writing process, the language used sounds credibly accurate.

Functionally, MARY SHELLEY is not a movie you see to be scared, it’s more of a movie you see to become informed. The originating back-story of how Mary came to conceive of and execute Frankenstein is more than a worthy one, even if it retroactively over-romanticizes Percy’s contributions. Remember, Percy was an unfaithful, philandering pedophile. Even if he wrote the bible himself, his character should never be exonerated, much less praised. Just because Mary saw this differently does not mean we should accept her decision as morally just, even 200 years later. Just because she forgave him does not mean we have to, or that the movie need condone it. One the other hand, it’s understood that without such gross mistreatment Mary would likely never have found the strength, courage and inspiration to write Frankenstein. But this is not a catch-22. Mary had talent as a writer prior to ever meeting Percy. She would have likely found her voice anyway. And yet somehow, MARY SHELLEY, in addition to feting the empowerment of masterful female authorship, too easily awards Percy off the hook. The only real credit Shelley ought to receive is giving Mary his namesake, not her authorial voice or career-defining character.

Follow the JOBLO MOVIE NETWORK

Follow us on YOUTUBE

Follow ARROW IN THE HEAD

Follow AITH on YOUTUBE